My name is Andrew Wildey and I have made mistakes. Some mistakes I regret but all in all they’ve served as some kind of learning experience. After all, what better way to learn an important lesson than to feel the sharp fangs of repercussion sinking your ass. Mistakes help you to find out where the pitfalls are and once you know them it affords you more confidence in how you operate. Here are a few goof-ups I’ve made and what I learned from them, hopefully making it far less likely that I’d ever have to go back and reshoot, or worse…

1. Sign on the dotted line

Back in DJing days someone would tell you about a gig, you’d roll up and play, and the promoter then turns out to be the biggest douche bag on the planet with their own warped ideas about music and their own interpretation of how much money was agreed. I learned that whenever I do anything make sure you agree on some kind of contract. For me personally, contracts have never been a means to hound someone for money, as I avoid working with shady characters anyway, but rather they act as a guarantee that reassures my clients of exactly what they’re going to be getting from me so when the final project is delivered it must be at least that level or we can renegotiate on price. Thankfully the prices have never had to change besides occasions where some very kind people offered to pay me double once they saw the amount of work I’d put in.

One easy mistake to make is when it comes to friends. When working for friends it’s easy to think “We know each other, so what’s the point”, but oh boy can that turn sour. They may be your friends but you have no idea of who else they might be involved with and how that might pan out. In these instances, you might even think “Well, no contract, no obligation”, which in law is true but hassle nonetheless. Contracts protect you. No matter what you’re doing you could potentially save yourself so much ass pain if you just have it down in black and white the who’s who and the what’s what. So contracts. Always contracts. Never mind Birthday cards, if your Grandmother won’t sign a contract she doesn’t love you.

2. Endless checks

Filming stuff is a lot of faff. You’ve got to get your gear, know how to use it and set it up properly, charge up like fifty batteries then travel to a specific location at a certain date and time to capture an event. There are a million technical and artistic decisions that can go into that and a million ways that things can go wrong. Big-budget Hollywood blockbusters are filled with gaffs and technical errors. In some cases, the entire film can require a reshoot like the Star Wars prequel “Solo”, when the studio decided that the direction was too comedic, or “All the Money in the World” when they had to recast Kevin Spacey after all those sexual misconduct allegations.

Sometimes you can just be plain stupid and forget to press record. When you’ve gone to all that effort to capture something on film it is imperative that you check. If you are working with other people then someone needs to take charge and ensure that everyone has everything set up properly. Correct frame rates, shutter speeds, ISOs, white balance etc… Trust and promises have no place in business, only checks and guarantees because let me tell you from experience that when you get that footage back and find it’s overexposed, out of focus or has some other weird issues, that feeling of having to go back to a client and tell them you need to reshoot is enough to make you curl up and die. And who knows if it is even possible to have the same light conditions or access to that location again. Either that or you try to fix stuff in post, but as I learned at sound school, if you record garbage then no matter what you do you’re going to be producing garbage at the end. So check.

3. Know What You’re Doing

My spirit animal Vincent Gallo defines art as creativity with no purpose. As soon as it has some purpose it stops being art. Sometimes it can be cool to just take a camera out to the woods and experiment to see what kind of stuff you can get. Sometimes these experiments act as a blueprint for a project you make in the future. For example the opening of “Dover: Make Yourself at Home” is essentially a remix or remake of an art collaboration with Lucy Brown called “Bvrn”, which studied a subject as they’re surrounded by a vortex of chatter. But there is a big difference between experimentation and going to film something with no clue as to what you want the final outcome to be.

With documentaries, unlike films, you can’t really storyboard or script as you aren’t there to manufacture something but rather to capture and document. But never the less you need to have a vision. You need to understand in broad or abstract terms what form the final structure will take and what the building blocks of that structure will be. For “Crobar: Music When the Lights Go Out” the film’s form was conceived on paper like a sound ADSR envelope, describing the different sections of the film in terms of emotional ramps and levels. The “pull the plug moment” was a carefully crafted event, not only in its structural significance within the film but also in the choice of archive footage projected onto a backstage metal shutter to give it a tangible physicality and the look of CRT television bars.

As with checking, you need to ensure that when you get that one opportunity to capture a moment, you don’t miss it. You have to ensure your frame rate, resolution and exposure are all just so and that you are standing in the right place at the right time. The gods of this are BBC wildlife cameramen who huck their gear to the most remote places in the world and then have to camp out for days and days just on the off chance of catching the slightest glimpse of that elusive mountain leopard. There is no clearer example of someone knowing what they are there to get and when they’ve got it. But go wandering out without a clue and you’re coming home with just tons of junk footage and the undesirable task of trying to then make head or tail of it, if that’s even possible. The more planning that goes into a project is always reflected in how better it comes out and how much easier it is to watch so get a clue.

4. Take Control

I never know what to call myself. Am I a camera operator, videographer, video producer, director? I’m kind of all of those things, but each has its own specific role. To be a director is different from being a camera operator or a producer in that you don’t need to necessarily touch a camera to direct, nor do you have to be responsible for the making of the film – you simply need to direct to ensure you capture on film that which you intended to capture. Unskilled or inexperienced directors take the role simply to mean yelling “action!” and “cut!”, but if you don’t take charge then you’re going home with footage that most likely could have been better with some extra directions given. You need to find a voice and learn how to manage people, instructing them on exactly where to stand and what to do.

My personal style of directing talent revolves around empathy – trying to understand where the subjects are at mentally and provide a frame of reference to direct them from their location to desired destination of the shoot. Talk through their performance to get the best out of them. As I always say “If you don’t look good, I haven’t done my job”. I also love to have fun when filming so the more jokes and laughs the better.

I have spent a fair amount of time in front of the camera in vlogs and with my old fitness channel where I recorded around 100 interviews, so I can totally understand and empathise with how your mind can go blank when staring into a lens with the record light lit. Happens to the best of us. Vanessa Kisuule is an award-winning slam poet, but even she had performance blocks towards the end of “Burst the Bubble”. I reminded her that she was the best at doing what she does, that there was nobody better, to not even worry about trying to remember the words because she already instinctively knew them, and just to focus on bringing the dynamite in the delivery and voilà, we struck gold.

The same applies in live situations where you need to stage manage to ensure there isn’t any junk getting into the frame. Most times you’re surrounded by people who are only too happy to help out but if you can’t communicate you’re going to have problems, so find your voice.

5. Own It

I appreciate this is supposed to be about how to avoid going back, but sometimes you just have to. It’s not always a bad thing either. Sometimes you may simply have reviewed footage and figured out a way of doing something better, got better gear or decided that something extra was needed. This is all part of the creative film making process and truth be told, more often than not, reshoots and additional shoots can often be some of the best stuff you’ll shoot because at that point you’ll be laser focused on what it is you’re trying to do and how to achieve it, so don’t sweat.

On rare occasions, something can just go wrong. For example, whilst filming “I Never Wanted to Hurt You” for Paula Jasmine James, I had just switched from a Ronin-S gimbal to a Ronin-SC, which unfortunately had come with a fault from the DJI factory that caused a micro-vibration on the tilt axis. As this was a ‘one-shot’ video, meaning the whole thing was done in one take, it rendered the whole shoot unusable. It took about twenty takes to get it, so knowing I had to request a reshoot gave me that sinking feeling. Thankfully Paula was an absolute babe about it and her grace was rewarded when the light on the reshoot was even better than on the original, even making it onto my showreel.

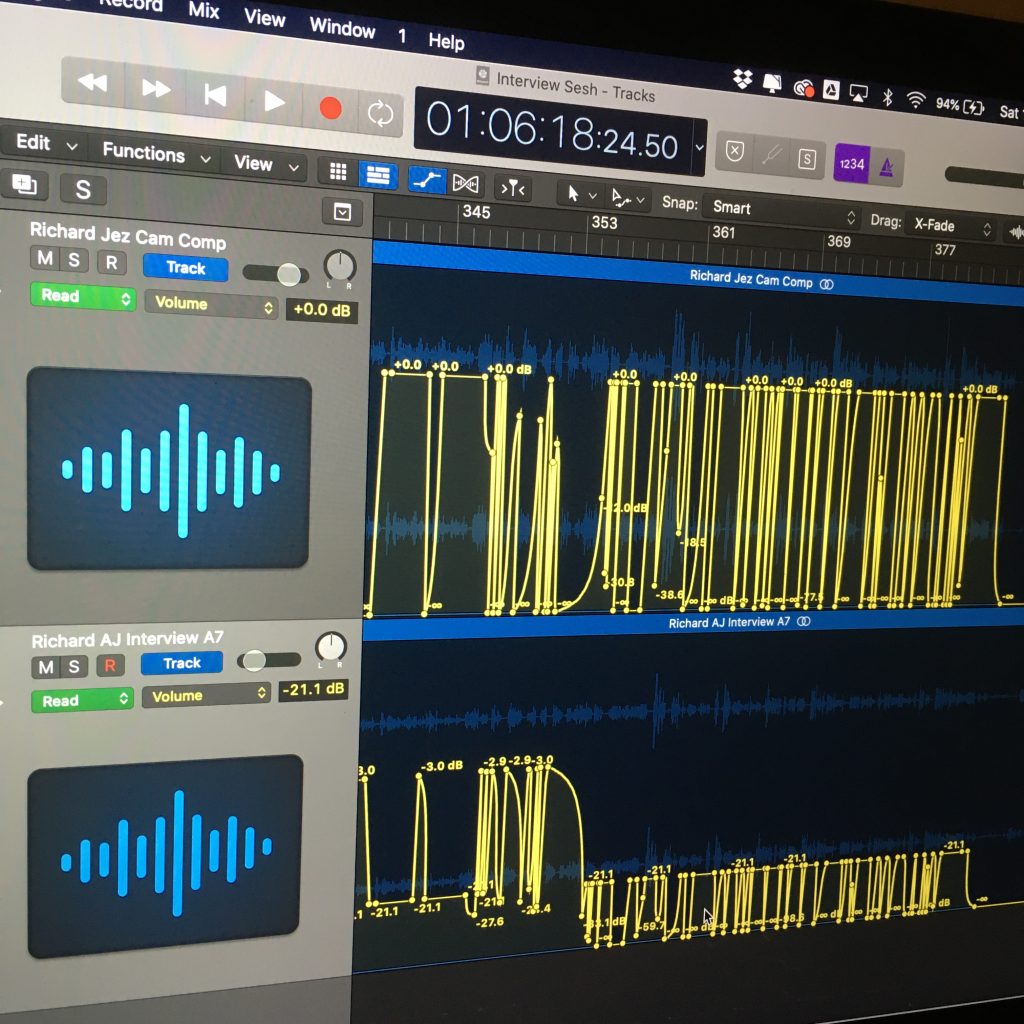

It really does help when you work with good people. But the same applies to entire takes or individual shots. If something goes wrong, just own it and correct it as soon as possible. There’s a lot you can do in post but not magic. One example of this was when I was involved in filming an interview as second camera and the assigned lead camera operator and sound recordist (an “all gear and no idea” charlatan if ever there was one) had placed the lav mic directly rattling against beads of a subject’s necklace! Despite the fact that this incompetent hack was wearing headphones the entire time and the recording was stopped twice to correct, when asked by the producer if the audio was ok he said it was fine. Well, as editor and sound mixer on that project let me tell you that it wasn’t, not by a long shot. The feat I pulled taking every click and clatter off that audio, in places hand drawing out compromised audio data with a pen tool, was nothing short of alchemy, but never again.

So I guess the main lesson is control. Filming can often get stressful and feel like herding cats, especially when you’re working solo on a hectic shoot. It can be tempting to just say “f*ck it!”, throw caution to the wind and leave it up to chance, but all that does is tempt fate to screw with you later on down the line. At every level, contractually, qualitatively and creatively always strive to maintain control and you’ll live a much happier life.